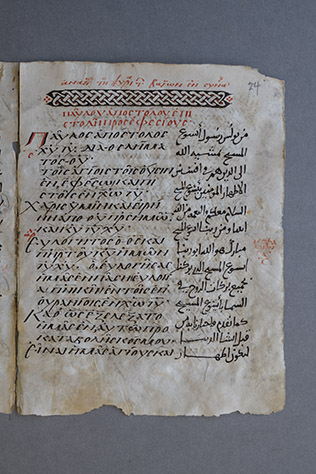

Sinai Greek New Finds Majuscule 2 is a manuscript of the Epistles of Saint Paul, in parallel Greek and Arabic. It has been dated to the latter ninth or early tenth century, and may have been written in Damascus. Folio 24 recto shows the beginning of the Epistle to the Ephesians. A rubric above specifies that this passage is to be read in the Synaxis on Palm Sunday.

In the sixth chapter of the Epistle to the Ephesians, Saint Paul wrote,

Wherefore take unto you the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand. Stand therefore, having your loins girt about with truth, and having on the breastplate of righteousness; and your feet shod with the preparation of the gospel of peace; above all, taking the shield of faith, wherewith ye shall be able to quench all the fiery darts of the wicked. And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God: praying always with all prayer and supplication in the Spirit, and watching thereunto with all perseverance and supplication for all saints. (Ephesians 6:13-18)

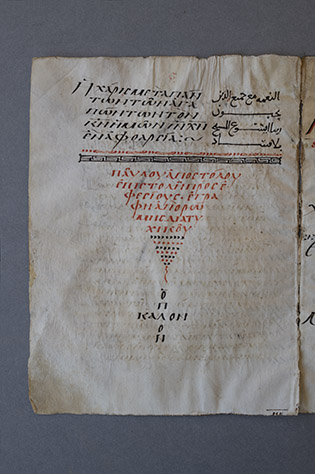

At the end of the epistle, the scribe has written two words, ὅπλον καλόν, ‘a good shield’. Each word has five letters, and they are written in cross form, sharing the central lambda.

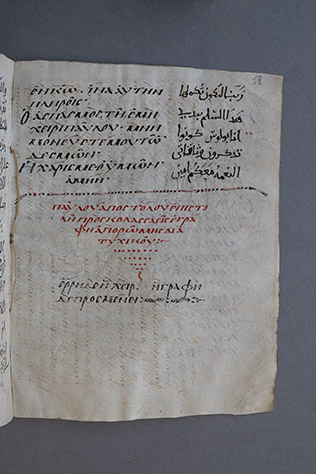

At the conclusion of the Epistle to the Colossians, the scribe wrote, ἔρρει δὲ ἡ χείρ· ἡ γραφὴ δὲ προσμένει, ‘the hand has collapsed, but the writing endures’. This is the perpetual lament of scribes, who deal with difficult materials and suffer from writer’s cramp. But the manuscripts they produce live on.

Dear Father Justin,

That is moving quote. Part of it, ” ἔρρει δὲ ἡ χείρ· ἡ γραφὴ δὲ προσμένει, ‘the hand has collapsed, but the writing endures’.” brings up my questions. I assume that most are written on types parchment and possibly paper of some fashion. Is there any routine maintenance of them in an ideal setting? Was any particular type of animal used? Was much use of vellum made? Did the species of animals change as time went on?

What type of inks were used and did it vary by date of the writing.

What types of writing instruments were like used and again, did it change with time?

With best regards,

Richard

These are far reaching questions. I can only give a few impressions. The best parchment was made from calf skin or sheep skin. Goat skin parchment has tiny dots across its surface, and was considered a very inferior writing surface. Making parchment is a complex process, and was carried out in metropolitan areas where large numbers of animals were already being killed for meat. The skin was cleaned, immersed in a lime solution, then stretched on a frame and shaved with a metal disc that had a burr on the edge. Parchment has always been expensive, but it is a beautiful and long lasting writing surface.

Carbon ink was made by collecting soot and mixing it with gum arabic, and then diluting it with water. Gall ink was made by taking the galls from oak trees. These were soaked in iron vitriol to yield an intense black dye, that was then mixed with gum arabic and water.

The text was written with quills made from the largest wing feathers of geese. The outer and inner membranes had to be removed, and then the feather was placed in hot sand to cure the quill. It was then cut to shape with a special knife. The curvature of the quill formed a slight ridge at the edges of each stroke, with the ink placed on the parchment between these ridges. In a detailed view of a page, we can sometimes see where the ink gave out and where the scribe dipped his pen in the ink to write again.

When we read a text, and admire the shape of the letters, we often forget all of the preparation based on long experience that led up to the act of writing.

Dear Father Justin,

I appreciate your reply. This is a fascinating topic. The labor and effort that went into these writings was enormous. I appreciate your efforts in preserving these works for future generations.

Regards and best wishes,

Richard

This is Byzantine minuscule, not classical majuscule. The cross at the bottom doesn’t say “good shield” but rather “noble tool” — ὅπλον καλόν (hoplon kalon), where ὅπλον means tool, implement, or weapon, and καλόν means noble, beautiful, or good.

The text itself reads:

Παύλου ἀποστόλου ἐπιστολὴ πρὸς Φηστοὺς ἔγραψεν Φιλήμονα…

Translating to:

“The epistle of the Apostle Paul, to Festus, written to Philemon…”

This isn’t a direct scriptural citation but likely a liturgical or instructional summary, referencing Paul’s communications — first to Festus (the Roman governor mentioned in Acts), and then to Philemon, as preserved or paraphrased by the scribe.

The phrase “ὅπλον καλόν” symbolically frames the recipient or reader as a “noble implement of the Word”, a common motif in Byzantine Christian manuscripts that emphasizes the believer’s role as a vessel for divine purpose — not merely a “good shield.”

Minuscule Greek became the dominant script after the 9th century, so this was most likely scribed between 1000–1200 AD. Further supporting this is the presence of well-developed early Naskh Arabic, which did not become prevalent until around 1000 AD.

In short, this manuscript was probably scribed in the early 1100s, after the founding of the Knights Templar (1119 AD), and the Arabic gloss was likely added during the Islamic Golden Age, possibly in the 12th or 13th century, as evidenced by the script styles and meticulous bilingual presentation.

I am glad that scholars are now turning their attention to what seems an important manuscript. It has the catalogue entry Ελληνικά Νέα Ευρήματα Μεγαλογράμματα 2. Gabriel Radle has recently published an essay with the title “The Liturgy of St James in Medieval Damascus: The Dating and Historico-Liturgical Context of Vatican Greek 2282,” in Orientalia Christiana Periodica, volume 87, 2021. He feels that Vatican Greek 2282, a liturgical scroll containing the Liturgy of Saint James, and the Sinai manuscript were written by the same scribe. If this meets with scholarly consensus, it would confirm an early tenth century date and a Damascus provenance for the Sinai manuscript.