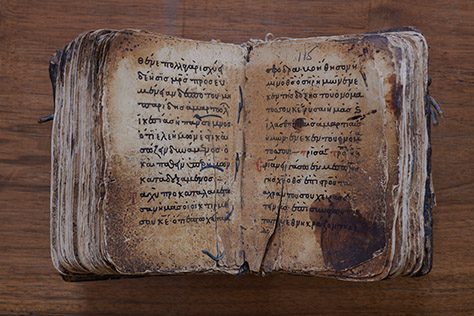

Sinai Greek 898 is an Horologion, written in the year 1335.

Sinai has beautiful manuscripts with brilliant illuminations, and letters executed in gold leaf that flash and gleam as the pages are turned. But the library also contains many humble volumes, generally small in size, intended for individual reading. The edges of the pages are stained from long use. Some of them have been repaired with whatever materials were at hand – bindings or even split pages sewn back together with thread in rough stitches. These manuscripts are no less significant, emblems of prayer and devotion, and witnesses to the austerity and privations of Sinai in centuries gone by.

From the Prayers of the Sixth Hour: Ταχὺ προκαταλαβέτωσαν ἡμᾶς οἱ οἰκτιρμοί σου, Κύριε, ὅτι ἐπτωχεύσαμεν σφόδρα. Βοήθησον ἡμῖν, ὁ Θεὸς, ὁ Σωτὴρ ἡμῶν, ἕνεκεν τῆς δόξης τοῦ ὀνόματός σου. ‘Let Thy tender mercies, O Lord, speedily go before us, for we are become exceeding poor. Help us, O God of our salvation, for the glory of Thy Name’ (Psalm 78:8-9).

Dear FatherJustin, Would books like this be made at St. Catherine’s or would It have been made somewhere in the Byzantine Empire? How was contact maintained with Constantinople after the Arab conquest of Egypt? Regards, Richard

It must have always been difficult to bring sheets of parchment or paper, together with pens, ink, and all the bookbinding materials, to this remote monastery. This makes us appreciate even more the manuscripts that we know were written at Sinai. These were more often humble manuscripts, for use in the services, for personal reading, or to record some treasured spiritual text. We have no formal histories for Sinai for the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries. But the material evidence points to continuity, especially in communication with Palestine and Syria. From the eleventh century, communication with Constantinople was restored. Travel, and the importation of materials, became easier.

Father Justin, Where did the monks at St Catherine’s come from through the centuries? My understanding is that currently the majority are from Greece. In the early days, did most come from Byzantine areas or from Egypt/the Levant? It seems that getting monks to Sinai would have been difficult. Thank you, Richard

From the fourth century, Sinai was an extension of the Holy Land, and thus a part of the Greek speaking world. Arab rule came to the Sinai around 630, but in all of its long history, Greek has remained the predominant language of the community. At the same time, Sinai was the destination of monks and pilgrims from the whole of Christendom, and in the sixth century, a pilgrim from Piacenza wrote that the Sinai monks were fluent in many different languages. In the tenth century, monks from Georgia lived in the area, translating many works from Greek and Arabic into Georgian. Many of the Sinai manuscripts in Syriac and Arabic were written in the thirteenth century. A thirteenth century liturgical scroll has the prayers read by the priest in Syriac, showing that this was his native language. But all the exclamations are in Greek.

Father Justin,

Thank you for all you do. In your opinion, what would be the defintive book(s) written about St. Catherine’s in English?

Here are three favourite books. The first is Through Lands of the Bible, by H V Morton, published in 1938, and reprinted many times since then. He begins at Tarsus, visits Ur of the Chaldees, and then takes a boat to Alexandria and visits the Coptic monasteries of Egypt. Chapter nine recounts his visit to Saint Catherine’s Monastery. He was a beloved travel writer, but he also did his homework, and understands the history of each place he visits. His account is both entertaining, and very informative.

The second would be Sinai, by Heinz Skrobucha, translated into English and published by the Oxford University Press in 1966. It is comprehensive, beginning with the earliest history of the peninsula, and continuing to his own times. He describes Sinai just before the construction of the modern roads and the invasion of the modern world. It is a wonderful book.

The third is History and Hagiography from the Late Antique Sinai, by Daniel Caner, published by Liverpool University Press in 2010. He has collected all the early accounts about Sinai, and presented them with discussions about contemporary scholarship for each text. It is an important compendium.

A 1964 issue, perhaps March, of National Geographic magazine introduced me not only to Sinai and S. Catherine’s Monastery but also to Orthodoxy in general. In my mind’s eye I can still see the photo of Father Elias (?) who seemed to embody the best of Orthodox monasticism. I think they had an accordion like photo of the mosaic of the Transfiguration which I cut out for my devotions.

Since I frequent bookstores and other venues I do look through mounds of Geographics for that issue which I like to give away to extend Saint Catherine’s influence for good.

Thank you for sharing